~~~~~~~~~~~~

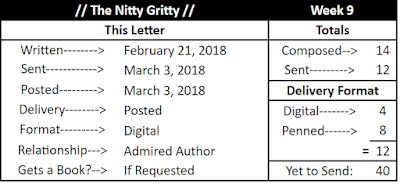

March 3, 2018

March 3, 2018

Dear Mr. McGrath,

I want to thank you for your fearless approach to unvarnished

Christianity in a historical context.

Nothing I’ve read has quite opened my eyes as wide as your much-needed,

unapologetic history of the protestant revolution—Christianity’s Dangerous Idea.

I’ve always believed in an objective truth. But for most of my life I also believed that

I had a better handle on it than anyone who didn’t interpret the Bible the same

way I was taught to read it. When you’re

raised in town of barely 100 people in a dry county in East Texas, there are three

kinds of people— those who go to church on Sunday, those who attend Wednesday

and twice on Sunday, and those who make a weekly beer run to where Texas meets

Arkansas, and only attend on Christmas and Easter Sunday.

The world was largely black and white— sin and right. I did visit or attend a pretty broad range of

protestant strains ranging from borderline legalistic Southern Baptist, to high

flying charismatic non-denominational institutions during my first 25

years. It was settled that Catholics

were on the fast track to hell, but the difference between the emotionally

driven and the dry, structured, expository approach to Evangelical Protestantism

was an intriguing mystery to me as a kid.

Why did the moving, emotionally-driven churches where we dared assemble

in scrums to pray for miraculous healing, and the Holy Spirit seemed to truly

interact with people, also have to be the ones with a tendency to flirt with

prosperity-gospel-esque ideas to the point of extortion? Why did the scripture-centric expository

churches that seemed more structured and transparent regarding finances have to

be so boring and spiritually “dry” by comparison?

To settle the paradox in my mind, I resorted to an

analogy. If as Christians of different strengths

and personalities we function like different members in the body of Christ, I

figured that different denominations, as collectives, worked largely the same

way . . . just on a different scale. Maybe

charismatic churches were like the heart— they served as the emotional centers,

while higher church, no less important, worked more like the brain. They were also deeply suspicious of each

other, like my own heart and brain have always been, so it seemed like pretty

sound reasoning at the time. I declared myself a Southern Methobapticostalyrian and moved on with my life.

It took living in 4 different states and coming in contact

with many, many people who think differently than I to realize I might not have

it all figured out. Moving every two

years for the previous six had left me without a long-term collective that I

had to dogmatically mesh with in order to belong,

and I think that helped afford me the courage to think independently, and deeper

than my roots. In the first couple of

years after moving to the Seattle area, where not only do Christians do

communion with real wine, but can recreationally enjoy alcoholic beverages

without even calling it communion (probably

around 2014) I found Christianity’s

Dangerous Idea at the public library.

There seem to be countless scripture-centric self-helpish

books geared toward Christians in our personal quests for holiness, based on

“safe” (mainstream) protestant dogma.

There are also publications (and collectives) that are militantly

anti-Christian. Ironically, the atheist movement

is becoming commercialized and institutionalized to the point that it’s virtually

an anti-religion religion in its own right.

The world has more than enough divisive, ideologically driven material

available for consumption and reinforcement of pre-existing dogmata. There’s not nearly as much scholarly,

matter-of-factual, historical perspective geared toward the intellectually

curious with boots on the ground beneath the ivory towers. Dangerous

Idea is a rare gem that bridges the gap.

I was fascinated to read about how the printing press helped

make the Bible accessible to the masses, leading to the protestant revolution—

the mass movement that quickly splintered into the countless denominations,

non-denominations, and cults that exist today . . . largely due to disagreements

over what the rules of the game should be regarding rituals, relationships, and

leadership, as well as the limits of grace and accountability. I have no doubt that the egos of prospective

shepherds played a huge role in this as well. They still do, of course.

To read about how recently in history usury was not a sin to

be taken lightly, given how churches today pay for country club style

campuses with massive mortgages, was an eye opener. My black and white system of belief was

challenged like never before by how fluid the institution has been from an

honest, big-picture perspective. The same

Bible that was once used to justify slavery, and is still used by some sects to

defend polygamy, is today cited by countless Christians to justify the denial

of services to the LGBT community. The

words haven’t changed. The whole

spectrum of denominations from fundamentalist to mainstream to progressive to

emergent evolve with culture, some right on its coattails, and others lagging

centuries behind.

Your book turned my world upside down and dropped me at a

crossroads. History drove home the fact

that I didn’t have it all figured out, but that wasn’t as shocking as realizing

that no one else really does or ever has, either. I’ve never wavered in my belief in an

objective truth, but I’m more convinced than ever before that no one will ever

grasp it completely, and to think we have

might be the most dangerous idea of all.

All we have is our perception of truth, shaped by what we are taught to

believe, experiences, and relationships.

Humanity is just extremely talented when it comes to getting lost in or

bent out of shape by details, then taking rigid positions galvanized by pride—

this is illustrated by the countless jagged lines drawn in the sand between what should be

considered outdated ceremonial law and acceptable behavior in the 21st

century.

The grace of God has to be more global in scope than I once

thought if there is forgiveness for our countless misunderstandings, not to

mention our arrogance in failing to acknowledge the array of planks poking out

of Christianity’s collective eye.

Forgiveness has to be greater than all of the fickle, divisive, and

error-prone attempts humankind has made in our attempt to grasp the nature and will

of the divine. We were either very wrong

200-300 years ago, or we are very wrong now. The petty things that divide denominations today, maybe even religions,

can’t possibly be enough to decide someone’s eternal fate if the grace of God

is more than hope imagined. The history

of the church helped me realize that I don’t have to know, or pretend that I do, in order to forgive or be forgiven,

love others, or have hope.

The fact that my eternal destiny used to seem only as

assured as my own personal level of confidence in the source of it seems a bit

odd in hindsight, but the unease that accompanies doubt makes the role of

belief and the intrinsic value of its accompanying sense of purpose crystal clear. How do you regain that settling foundation

that faith affords after finding the will to question your own reality? To put it in East Texan, I’d done gone and thought

too much. I could no longer view my

purpose in life as a challenge to win over as many people as possible to my personal

interpretation of a book that was written by men, and has evolved in meaning from

generation to generation for centuries.

I felt a bit like Christian from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress— if Morpheus had met

the protagonist along the path and convinced him to swallow the red pill. I was out of the matrix, but I was no

Neo. I wanted back in, like Cypher, to again

taste that juicy, figurative steak of certainty that was the basis of community as I knew it,

and offered a profound sense of purpose . . . but how?

It was a lonely place to be when I couldn’t comfortably talk to a

majority of the people I love about the faith that I was working out “with fear

and trembling” because they would instantly tremble and fear even more— for me.

It takes a rare breed to unemotionally explore new ideas that contradict

what they’ve always believed, without citing references to the very

book that no longer has me spellbound.

Besides that, if someone is happy and secure in their mainstream

translation, despite the fact that I might feel desperate for them to

understand me now as deeply as they did before, spawning a crisis of faith in

someone else who’s not ready to go down the rabbit hole and consider alternate

realities hardly seems responsible. To

attempt that is more likely to wound relationships than foster

understanding and bring us closer together.

I have to say that it’s a good way to get people to pray for me, though.

My outlook on life changed, by necessity, from a predestined

journey with a preferred route outlined by a modern translation of a

leather-bound road atlas, to a grace-centered adventure. I was free to think and consider new ideas. I could listen to and try to understand others

without taking them to task with my interpretation of scripture. I realized how annoying it is to be on the

receiving end of that when you don’t buy in to biblical literalism. It’s like trying to apply the law of gravity to me in the international space station.

I’ve personally been able to largely settle on Paul

Tillich’s definition of God as the “ground of being,” rather than the

intergalactic melding of karmic Big-Brother, Santa Claus, and Mother Theresa

that I had imagined for most of my life.

He impresses me as a philosopher, and yet a Christian— much like you do

as a historian who has kept the faith without fearing the facts. I didn’t read up on you until after I

finished your book. So, when I did, I

was surprised to learn that you are a Christian and a scholar. I’d

automatically assumed that as an intellectual who was unafraid to take the

blinders off and look history in the eye, you probably crossed over at some point to a form of

agnosticism like Bart Ehrman. From what

little I know about you, your religious trajectory actually seems the inverse

of his.

I’m still working on the best way to approach scripture with

a completely different mindset toward the Bible. If you make it to Seattle, let’s get a Guinness

. . . or some Bushmills . . . coffee or tea if you happen to be a purist. I would love to understand how you personally

hold on to a faith that keeps you grounded and lends purpose to life, knowing

what you know about the history of the church, how much it has changed since the

mass movement started by Jesus of Nazareth was institutionalized, and the obvious

impossibility of “right belief” in light of history.

Your account helped open my mind by expanding the scope of God’s mercy, and lead to the distillation of my own faith from a stone pillar of destiny and laws to a scarlet thread of hope and grace-centered love. Thank you for fearlessly making the history of the church accessible to folks like me, and trusting truth to run its course.

Your account helped open my mind by expanding the scope of God’s mercy, and lead to the distillation of my own faith from a stone pillar of destiny and laws to a scarlet thread of hope and grace-centered love. Thank you for fearlessly making the history of the church accessible to folks like me, and trusting truth to run its course.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What do you think?